How LVIAs Can Support Biodiversity Net Gain

Beyond Metrics: Why LVIA Still Matters for BNG

At first glance, BNG may appear to sit firmly within the ecological domain, led by habitat surveyors and biodiversity consultants using GIS mapping and DEFRA’s metric tools. However, biodiversity is not just a matter of unit counting—it is also about habitat integration, landscape context, long-term viability, and perceptual experience. These are precisely the domains in which LVIA Assessment work operates.

Whereas BNG focuses on quantifying ecological uplift, LVIA contributes to understanding:

-

How well new habitats integrate with the existing landscape character.

-

Whether proposed planting or land use changes are visually appropriate.

-

How mitigation and enhancement measures can contribute to both ecological value and visual amenity.

-

Whether BNG proposals respect the historic and perceptual qualities of the site or setting.

GLVIA3 and the Role of Mitigation Planting

GLVIA3 (and reinforced by LITGN 01/24) requires assessors not only to assess the effects of a proposed development but also to consider mitigation—especially landscape mitigation designed to reduce, offset or compensate for harm. This typically includes:

-

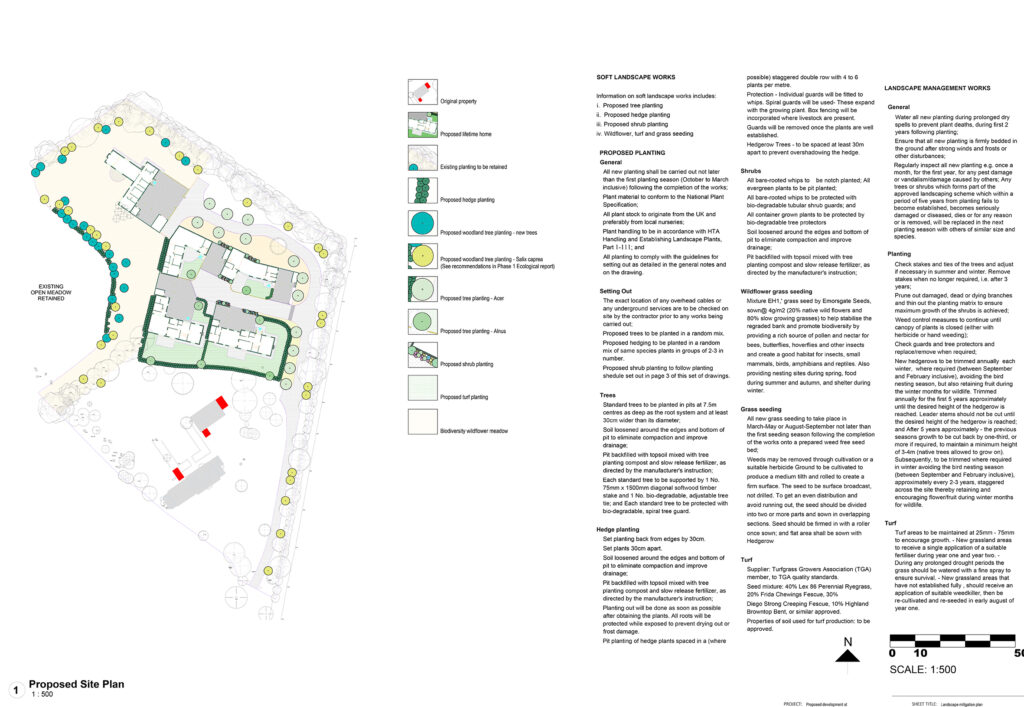

New native woodland, scrub, or hedgerow planting.

-

Meadow creation or species-rich grassland management.

-

Pond and wetland design to soften built form and support visual interest.

-

Landform modelling or screening bunds with habitat potential.

Many of these interventions also contribute directly to BNG calculations. This means LVIA mitigation is not only serving a visual or perceptual function, but also delivering measurable biodiversity value—a dual benefit that can be critical in constrained or controversial schemes.

However, to be effective, this integration must be deliberate. It requires early-stage coordination between landscape architects, ecologists, and design teams. It also requires an understanding that BNG is not about ecological ‘islands’, but about habitat networks that support wildlife movement and landscape coherence.

Coordinating LVIA and BNG from the Outset

Too often, BNG proposals are prepared late in the process, added after the development design and LVIA are well advanced. This siloed approach risks duplication, contradiction, or missed opportunities.

A better model is early landscape-led masterplanning, where the LVIA informs:

-

Which areas of the site are best suited to biodiversity enhancement.

-

How mitigation can double as habitat creation.

-

Where visibility is a benefit (e.g. public engagement) or a constraint (e.g. sensitive receptors).

-

How site layout can support ecological corridors and landscape coherence.

For example, an LVIA may recommend a tree belt to screen a development edge. Working with the ecologist, that belt could be diversified in species composition, extended into a wildlife corridor, or linked with existing hedgerows to enhance both visual mitigation and biodiversity score.

Contact form