Understanding Zones of Theoretical Visibility (ZTV): What They Are and Why They Matter

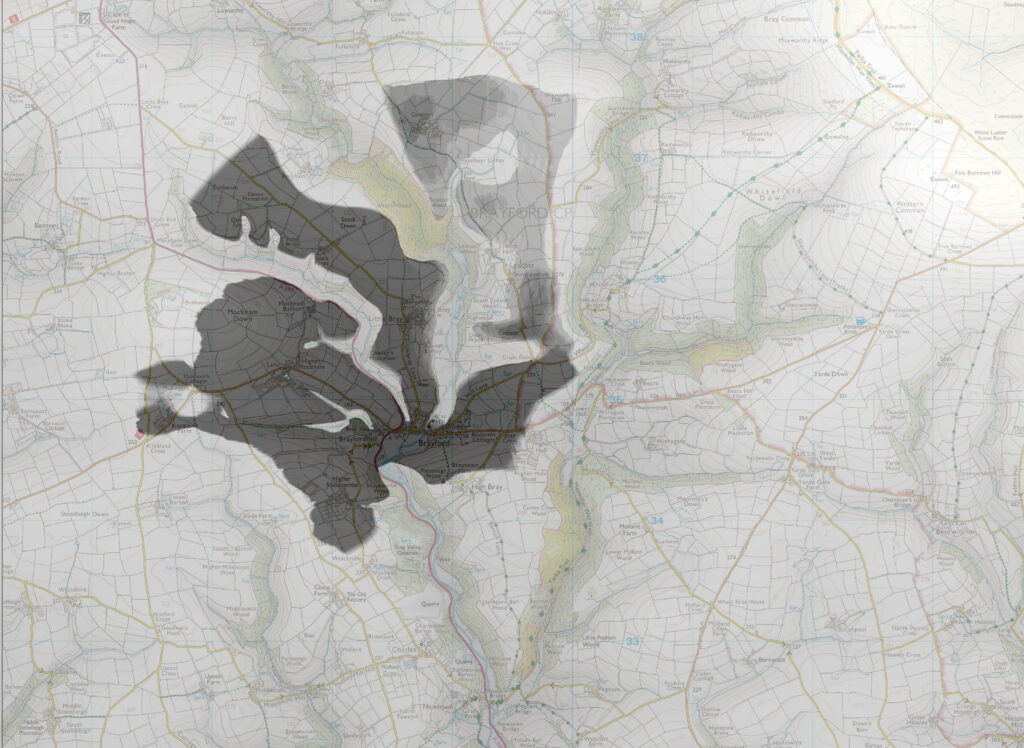

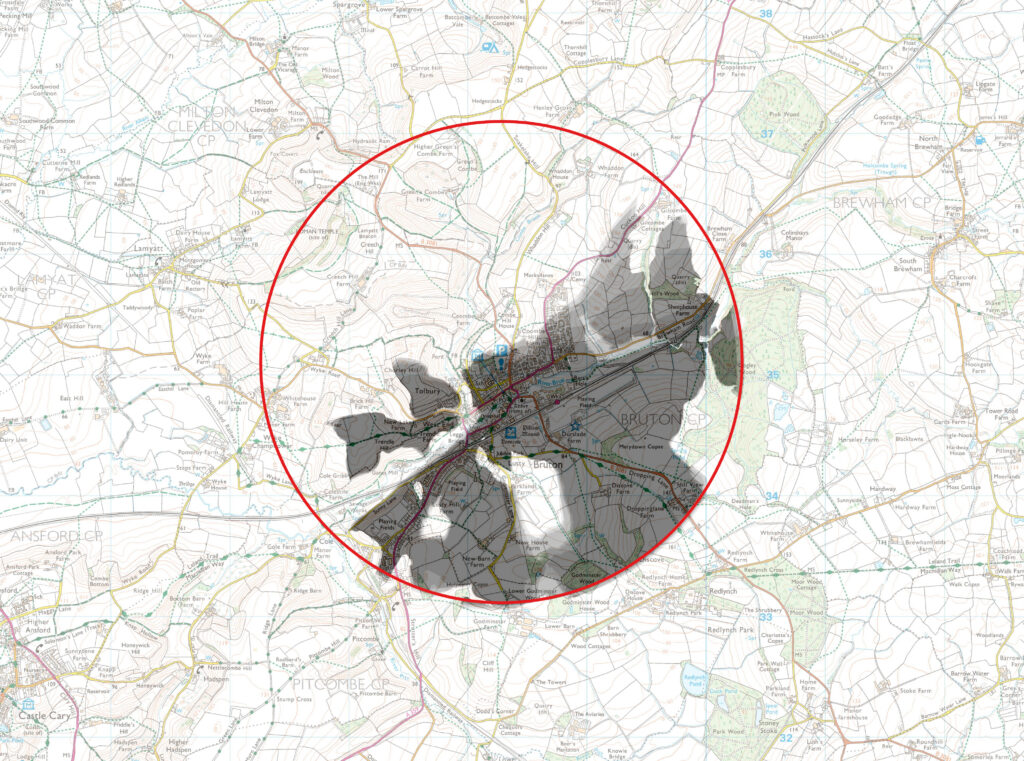

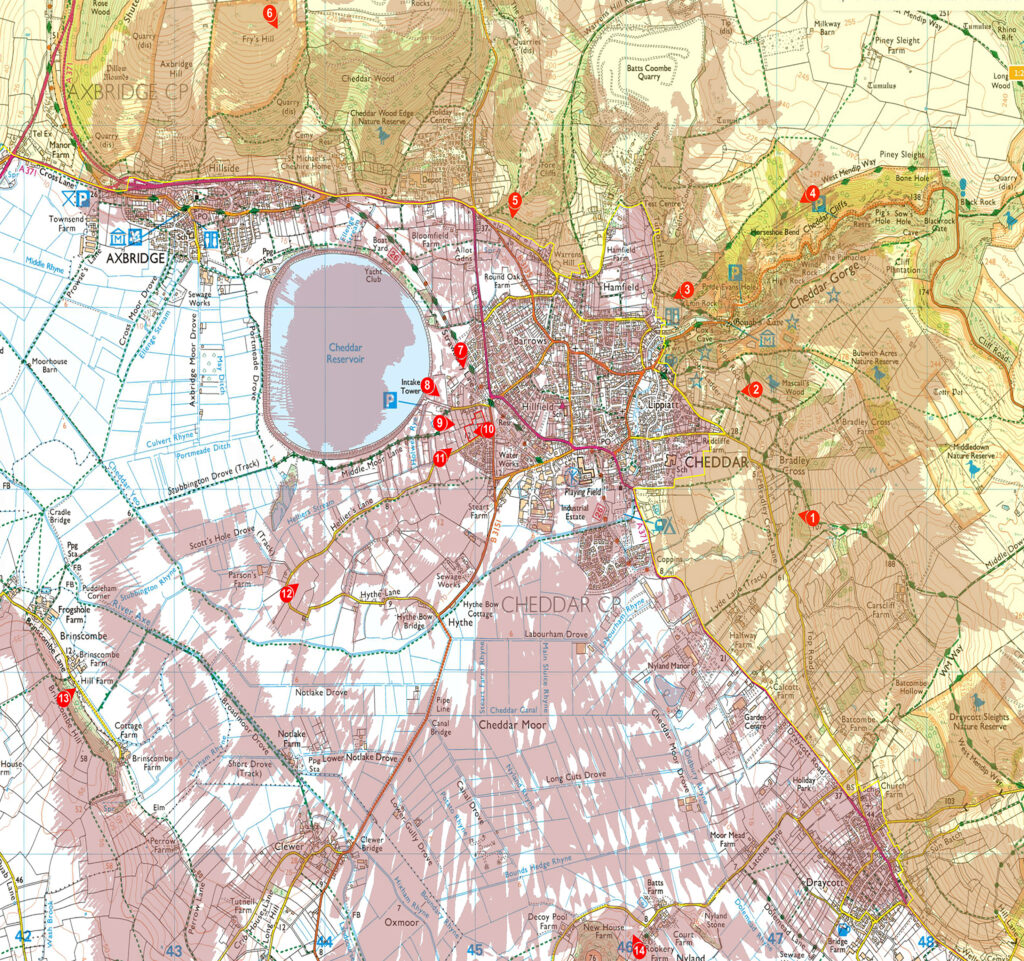

When conducting a Landscape and Visual Impact Assessment (LVIA), an important tool in the process is the production of a Zone of Theoretical Visibility map, commonly abbreviated to ZTV. These maps are fundamental to the process of understanding how visible a proposed development may be within a given landscape and, in turn, the degree to which it may affect landscape character and visual amenity.

In this post, we will explore what a ZTV is, how it is produced, and, most importantly, why it matters—especially in the context of robust LVIA Assessments.

How Is a ZTV Used in LVIA Assessments?

In any comprehensive LVIA Landscape report, a ZTV plays a central role in shaping the scope of the assessment. It helps determine:

-

Viewpoint Selection: By identifying potential receptors across a wide area, a ZTV allows landscape consultants to choose representative viewpoints for photomontages and analysis.

-

Extent of Visibility: Understanding whether a proposal will be visible only in its immediate surroundings or across a wider regional context is essential in determining its scale of impact.

-

Stakeholder Engagement: ZTVs are useful for communicating with planning officers, local communities, and statutory consultees such as Natural England or Historic England, particularly in relation to designated landscapes or heritage assets.

Moreover, in projects subject to Environmental Impact Assessment regulations, ZTVs are often mandatory components of the visual baseline and are included as appendices or figures in the Environmental Statement (ES).

The Role of ZTVs in Planning and Design Evolution

Beyond assessment alone, ZTVs also have a valuable role in the design evolution process. By mapping zones of likely visibility, project teams can make informed choices about siting, orientation, scale, and screening measures at early stages—thus minimising harm to landscape character and visual receptors before a formal planning submission is made.

For example, relocating a structure just a few metres downhill or adjusting its height could significantly reduce its visibility in sensitive areas. This proactive approach often results in better design outcomes and smoother planning pathways.